Neurodiversity in the Workplace: Social Expectations

Social Expectations

For years I had the feeling that the message I was supposed to be delivering wasn’t quite right. I would see in management books and training materials the team mantras of work together, socialise, share everything, become one unit, engage and connect . Whilst training team leaders on management programmes, I would hear time and time again complaints about team members who weren’t considered to be sufficiently social. Comments such as:

“He won’t come to the pub for a few drinks after work.”

“She never joins in when there’s a birthday to celebrate."

“I hardly notice he’s there sometimes."

“She looks irritated when people pop over for a chat when she’s working, but always interrupts others and says the wrong thing.”

“He’s rude!”

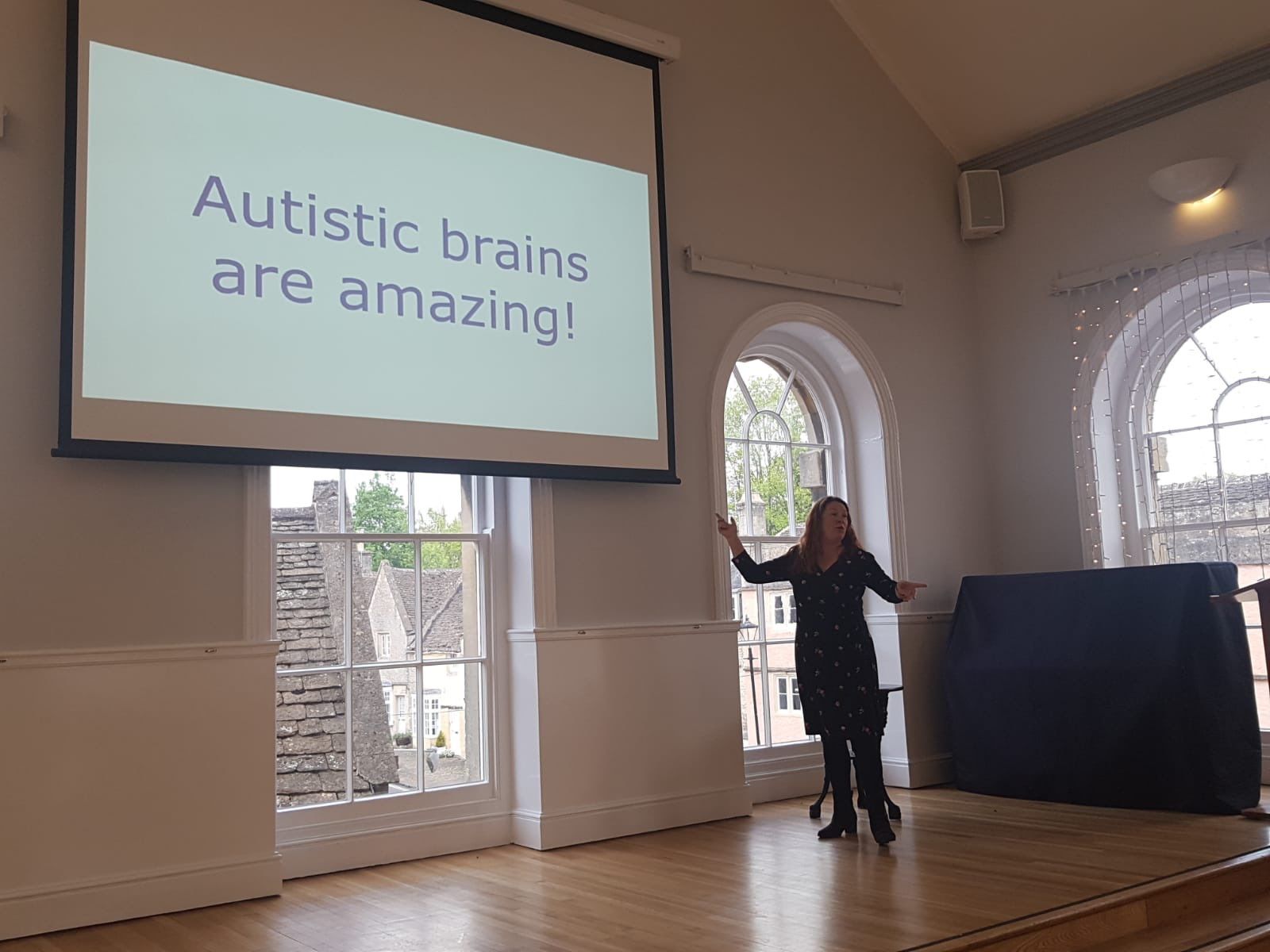

Let’s be clear. Social interactions are hard work. Knowing what to say, in the right way, at the right time and to the right person takes a lot of focus and energy in people whose brains haven’t developed in a typical way. Autistic brains function differently, and a key feature of the lengthy diagnosis procedure is identifying social difficulties. This means Autistic people won’t always respond in expected ways or prioritise their own or other people’s social needs. Every Autistic person has social difficulties – that’s partly why they have the diagnosis. It’s a good time to mention there are millions out there who are Autistic but haven’t been diagnosed or recognise that fact themselves. The challenges and behaviours are present with or without a letter of diagnosis.

The pattern and manifestation of these social difficulties varies. There’s a scale from the person who shuns all but essential contact to the Autistic extrovert who constantly seeks social contact. Remember that social contact includes not just conversations and relationships, but text messages, attending meetings, sending a greetings card, answering the phone to strangers, tweeting, buying something in a shop, and greeting a family member.

The Shunner and the Extrovert

The Shunner may intensely dislike social contact and believe that they really don’t need small talk and companionship to function effectively. They may, however, have been so rejected by society that they’ve abandoned being social. It you’re a little bit quirky, rejection can come from all directions and be overwhelming. From passing comments, glares when things are said out of turn to direct insults and declarations of weirdness. We can be seen to get it wrong through over-sharing, unacceptable words, unexpected emotions or mis-timing when to speak. We may sound different, perhaps monotone or with irregular pacing of words and sounds. Society today really can slam down hard and fast on those who don’t quite fit in. Society quickly forgets that it’s those who didn’t quite fit in and worked to a different set of boundaries that have created some of the world’s most important inventions and who continue to innovate at the highest levels.

At the other end of the scale is the Extroverted Autistic. They might step forward for every social engagement, be the first to arrive and the last to leave, but there’s a good chance they’re not quite getting it right. Socialising requires some very fast and very complex processing by the brain.

Simply responding in the right way to “Hello” requires these steps, plus a whole lot more things that the Autistic brain isn’t great at:

-Recognition a message has been directed at you

-Processing of the sound into meaning

-Identifying the person through facial features, location, smell and sound etc

-Identifying the threat level from tone, body language and environment

-Deciding an appropriate response

-Process the emotions of the situation

-Positioning the body, face and vocal chords to deliver the reply appropriately

-Prepare to deal with the response

Put all of that into a party situation and the difficulties escalate exponentially. Who to talk to? Where to sit? What to laugh at? What to say? What not to say? How to say it? When can I escape?

Autistic people are often constantly struggling with sensory input, such as lighting, the feel of clothes and smells. Most are running on constantly high anxiety levels, perhaps in a state of alert or mild panic, with thoughts and worries churning around their minds. Social interaction adds to the heavy load they are already processing. Some manage this well, others don’t.

Social anxiety is crippling, and it goes way beyond just shyness. If something is hard, takes a lot effort and isn’t always rewarded we may avoid it and become anxious at the thought of doing it. If it’s something we’re forced to do or persuaded ourselves to attend, having social anxiety increases the chances of getting the interactions wrong.

Ways to help in the workplace as a manager or colleague:

-Remember that many people come to work to do a reasonable job, get paid and go home. Not everyone wants to be a social superstar. If they’re meeting targets and no-one’s complaining all’s fine

-Think about the social demands you’re placing on the team or your colleagues. Are they necessary or just making you feel good?

-Encourage comfortable and positive social interactions and events that make people feel good about themselves. Being made to build and then fall off a raft into a freezing lake, hold hands with colleagues on an assault course, and then cram fully dressed into a hot tub with 9 other people to celebrate ‘being the best’ was not the most enjoyable experience of my career.

-If they’re not managing basic interactions, such as responding on time or going to meetings, explain why these things are important and find out what adjustments could be made to help

-Be prepared to give time for them to make decisions over social requests. Explain what’s expected and don’t force things if the answer’s no.

-Model appropriate social behaviour. Do you greet everyone (hugging is often a no-no!) in a way that makes them comfortable? How do you respond when interrupted? What emotions are your facial expressions leaking? We don’t have to be emotionless in the workplace but oversharing can be exhausting for everyone.

-Autistic people often have unusual obsessions and hobbies, as their brains are often great in specialising and over focussing. Show an interest and don’t judge. The most recent hobbies I’ve come across include ancient Greek Gods, the history of Samurai weapons and road kill taxidermy.

-Signpost to HR, Occupational Therapy or a GP if you think the person is becoming overwhelmed by their social anxiety at work

-And finally, find a quiet, comfortable low stress time to ask the person what can best help them. Don’t’ make assumptions, as they may well surprise you with the simplest of things that could help.

Always remember that what is socially important to you may not be important to somebody else. They're not wrong, just different.

by Helen Eaton

Through her work, Helen Eaton (MSc, PGCE) has gained an unusual and fascinating insight into both lifelong education and the workplace. She combines over 20 years’ experience delivering management training to the UK’s leading IT and Finance companies with a passion for education and a teaching qualification. Specialising in Neurodiversity she has worked with many families and professionals, promoting the importance of understanding and supporting Autism and Specific Learning Difficulties. Most importantly, she has a Neurodivergent family and rejoices in the uniqueness of their Autistic, ADHD and Dyslexic minds.

If you reproduce or share this work please acknowledge the source and the author.