Socialising

Everyday life requires a vast range of social skills, whether simply spending time with family members, shopping or building friendships. All communication, whether its face to face, by telephone, text or social media requires social thinking. This includes recognising and receiving the message, processing it, and choosing the appropriate behaviour, emotion and reply.

Most human learning is done socially – from watching and communicating with other humans. Children need to spend time with other children and adults in order to learn. This includes learning what’s safe or dangerous, how to do everyday tasks, through to learning new sports and hobbies.

Social thinking can be very hard and very tiring for Autistic children. An Autistic brain seems to struggle with learning and remembering social behaviour, boundaries and responses. So, it can be difficult for an Autistic child to understand and remember how they should behave, how to express their emotions and ask for what they need.

It’s true that they may not need as much social contact as other children in order to thrive and be happy, often preferring to be more self- contained. The opposite may also be also true as some enjoy spending a lot of time with other children and adults.What’s true for all of them is that the more they avoid or are excluded form socialising the harder it is, and the less confident about doing it they become.

Social difficulties in Autistic children range from mutism and a ‘disconnected child’ through to a very articulate and able child who may appear at times ‘socially awkward or odd’. They might also have additional speech and language or developmental difficulties affecting their social skills and behaviour

An Autistic child may:

·get impatient with children who can’t who keep up with their ideas or understand the rules

·try and control play, prefer to play by themselves or stick to the same toy or games

·enjoy staying on the edge of groups, just happy watching

·be too physical or say things that cause upset

·prefer to stick to one friend, or move between groups without really belonging to any

·get upset very easily when playing

·not worry about following the latest fashions, trends, or looking a certain way in order to fit in, or do the opposite and copy other children’s appearance or behaviours to an extreme level, particularly in teenage years in order to try and fit in

What’s true for all of them is that the more they avoid socialising the harder it is and the less confident about doing it they become.

It is crucial that Autistic children have the opportunity to enjoy successful social

experiences. Enjoyment is the key word here. This isn’t about forcing the right

response or behaviour but finding environments and situations where an Autistic

child feels comfortable, safe and can join in as much or little as they want

to. Depending on the child, success may mean enjoying a family dinner, paying

for something in a shop, joining a new club or finding a new friend.

We need to look at each child and think about what social skills would be most

helpful to them. The range of Autistic difficulties is so broad that some may

be capable of having perfect manners, but for others it’s more important that

they are confident to ask an adult for help when needed.

We can make it easier for Autistic children to socialise by:

· ensuring they are not tired, hungry or physically uncomfortable when socialising, as sensory distractions add pressure

· explain what is happening, how long it will last and how it will end, e.g. a party

·build in an ‘escape plan’ - it may not be needed but it’s reassuring to know it’s there.

·let them play freely at their own pace in their own way, avoiding being overly critical

·build in opportunities to learn about sharing, turn taking and asking people for things – all useful life skills

· allow time to rest and recover after social activities

·actively celebrate success - if an Autistic

child realises something went well, and they feel good about it, they are more likely

to try it or something else new

· remember that what is fun for us isn’t necessarily fun for someone else. We all have different versions of fun.

·finding a balance - enough socialising to feel wanted, loved and able to enjoy time with other people, but not too much so that they feel overwhelmed or panicked.

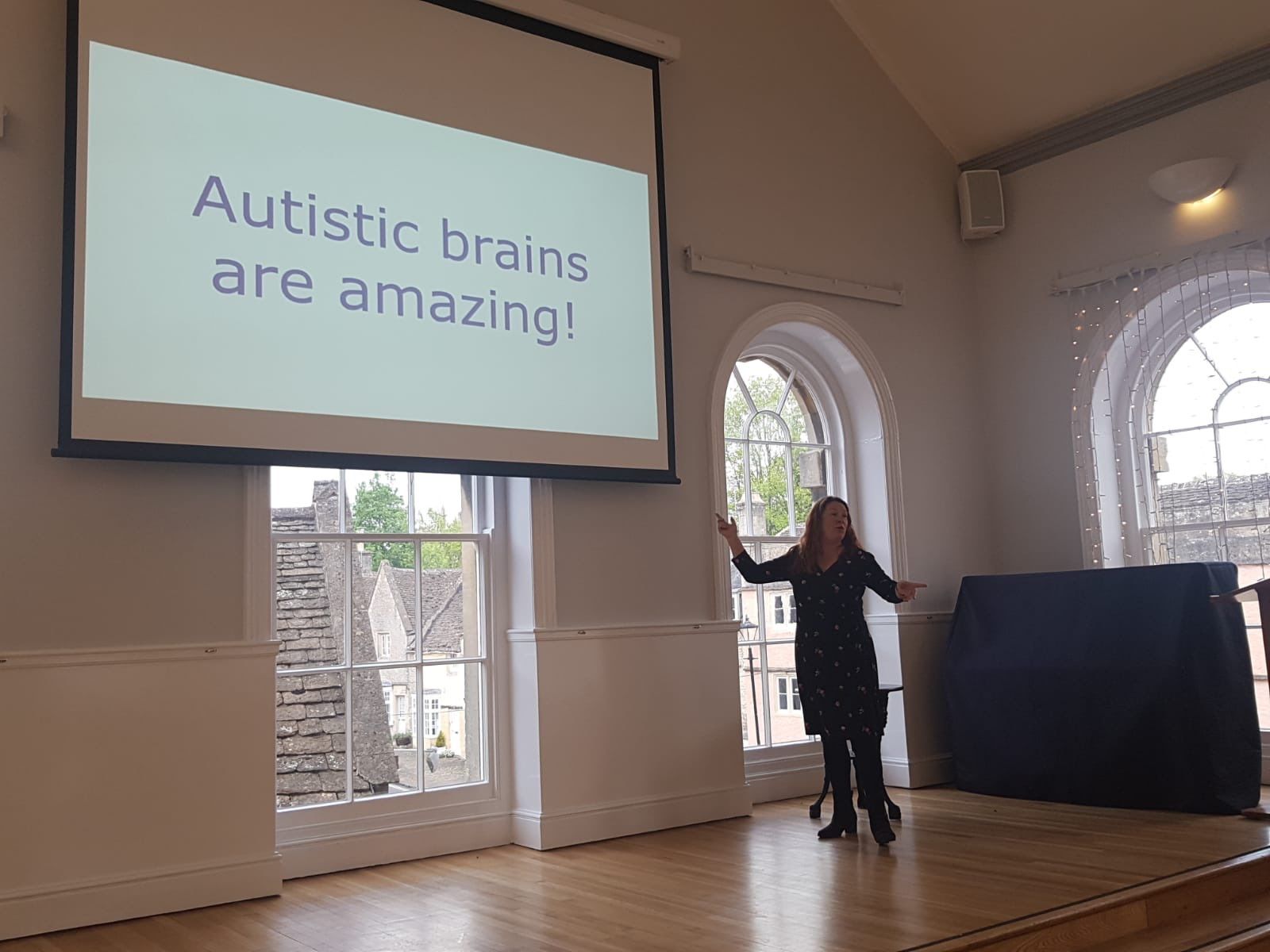

by Helen Eaton

Through her work, Helen Eaton (MSc, PGCE) has gained a fascinating insight into both education and the workplace. She combines over 20 years’ experience delivering management training to the UK’s leading IT and Finance companies with a passion for education and a teaching qualification. Now specialising in Neurodiversity, she has worked with many families and professionals, promoting the importance of understanding and supporting Autism and Specific Learning Difficulties. Most importantly, she has a Neurodivergent family and rejoices in the uniqueness of their Autistic, ADHD and Dyslexic minds.

If you reproduce or share this work please acknowledge the source and the author.